Dividir, compartilhar, era, e acredito ainda é, o princípio, meio e fim desse nosso bendito vício.

Hening é fundador do conceito de surfista preocupado com o futuro do planeta, com a Surfrider Foundation e agora, nem tanto agora, ataca com a Groundswell Society, uma comunidade de pensadores ouvindo e falando de assuntos que a imprensa ignora ou desconhece.

Clicando no título, voce é lançado direto para o saite e tem a chance de ler, em arquivos PDF, os temas do encontro de 2002. Me perdoem o texto em inglês, mas creio que a turma, se não domina, compreende.

Fundamental.

Como a água salgada.]

The Stain on the Soul of Surfing

by Glenn Hening

The locals had a reputation for short tempers, thuggery and a ruthless pecking order. That meant little to the invaders, whose ego-driven arrogance was fueled by a self-image saturated with superiority. The two sides clashed in a violent confrontation. The uninvited visitors were beaten back, and the locals showed them no mercy.

Now where in the world of modern surfing did this happen? Velzyland? Cactus? Palos Verdes? Burleigh? Stockton Avenue? The Canaries? The Ranch? Narrabeen? Could be any one of dozens of intense surf spots around the globe, couldn't it?

But no, the above is not about a specific example of surfer localism per se. It's about the single most violent episode in all of human history: the battle of Stalingrad during World War II. The Nazi army had advanced rapidly for a thousand miles deep into the Russian heartland when Soviet dictator Josef Stalin told his generals that there would be no more retreat, and that

they were to stand their ground to the death. And thus were revealed deep-seated human instincts of conquest, violence, and revenge, resulting in the deaths of almost a million soldiers and civilians in a little less than six months.

What greater contrast could there be? Warfare-to-the-death that destroys a city is about as far as you can get from riding aqua blue energy in warm water along beautiful coastlines, where the power and the visions provided by our mother ocean combine to make surfing an almost religious experience. However, if our sport/art is indeed so wonderful, then "surf rage" reveals something that, I contend, is born of the exact same primal instincts that caused ten thousand deaths a day during the siege of Stalingrad. That was man at his worst, and violence amongst surfers, blessed as we are by Nature, is pretty much in the same category.

Voce está disposto a dividir essas ondas ?

If you think that comparing Nazis and Soviets to surfers is a bit of a stretch, then consider the following from the Los Angeles Times dated March 26, 2000. Titled "Drought Desperation", the article relates the story of a battle between monkeys and humans when water trucks arrived at a drought-stricken trading post in northern Kenya. When the monkeys saw the water, they attacked so ferociously that the humans were forced to retreat as the primates quenched their thirst. But the humans re-grouped and fought back the simians with axes and machetes. Sounds like the first day of waves after a long flat spell at Sunset or Swamis or Kirra, no? And you can take the simile even one step further when talking about conflict over water: there was a once fight involving a machete at the Ranch, where gunshots have also been used to intimidate outsiders.

All this is by way of introduction to my take on what has been the single most shameful and disgraceful aspect of our sport/art for the last forty years. One has only to talk to those who have quit surfing in disgust, or those in the non-surfing public who are unable to comprehend how surfers can reveal such base human instincts when they are so blessed by the ocean, to understand how localism and violence have stained the soul of surfing.

In early April of this year Chris Bystrom called with the idea of my writing about "surf rage" in response to the recent assault on Nat Young. His account of what had happened was pretty depressing, especially since at the time I was writing up a summary of Surfrider's Clean Water Classic event at Rincon, where we are able to run a weekend contest in great waves without security or water marshals and with the full cooperation of all the local Santa Barbara surfers. (see accompanying article)

Yet here was Chris describing Nat's serious injuries caused by a conflict in the water at Angourie. So on one hand I was filled with the satisfaction of being a part of a wonderful event where hundreds of surfers cooperated in sharing great waves at one of the most crowded breaks in the world. But on the other I was sadly reminded that surfers are also capable of being reduced to the level of primates by their selfishness and lack of self-control.

Surfing is as pure a pleasure as anything we do on this planet. The beauty, the sensation and the physical challenge of riding waves are unmatched by any other sport. But surfing's internal conflicts are also unique. They affect our surfing lifestyle across the board. In fact, it seems as though our "culture" is bookended by bullshit.

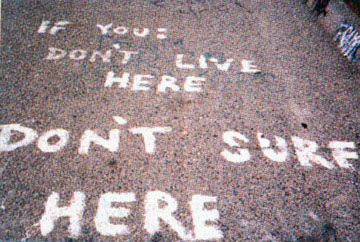

No Quebra-mar ou no Arpoador, a frase se repete com a caligrafia dos semi-analfabetos

At the Neanderthal end, we have our mossbacks (a deprecatory term for old, set-in-their-ways sailors, referring to turtles who've been in the water so long that moss grows on their shells). These guys never actually live at the public surf spots they call their own, but since they usually have no where else to go in their lives, they resent anyone showing up at "their" beach, public be damned. When intruders start riding "their" waves, they start growling with indignation like bull walruses whose cows are being eyed by rivals. They rage with jealousy as if surfing was their substitute for sex, and their aggressive attitudes lead them to commit senseless crimes of passion when they cut off strangers, challenge them to fights, and worse.

At the other end of the spectrum, where professionals make their living off the sport, things are often no different. I have immense respect for Nat Young, a pioneer of advanced surfing equipment, a former world champion, a writer of surfing books, and an acknowledged leader of the surfing tribe for three decades. But Nat has always been aggressive in the water, and he lost it completely

when 18-year-old Luke Hutchinson got in his way. Now Luke is no angel either, and things escalated quickly. Today Nat is recovering from injuries sustained when Luke's dad lost HIS sense of membership in the human race and attacked Nat mercilessly. And that is only the most recent incident amongst the leaders of our sport.

There is the little-known episode involving Johnny-Boy Gomes, winner of $56,000 at a 1998 Pipeline contest organized by his friend Eddie Rothman. It was the biggest first-place check ever in a surfing contest, placing Gomes at the top of the heap as a professional surfer. But only a few months later, Johnny-Boy was told to go back to Hawai'i by community elders after attacking a young local surfer at a beautiful Polynesian reef.

And who can forget another landmark incident: the 1994 World Longboard Championships at Malibu. A veteran 'Bu kneeboarder didn't get out of the way fast enough when the contest started, and so Rick Ernsdorf was hospitalized after being held underwater by Joe Tudor and then having his face pummeled bloody by Lance Hookano.

If you consider that few, if any, veteran waveriders have not seen hostile graffiti, felt the rats-in-a-cage vibe of overcrowded surf spots or witnessed real violence, it becomes apparent that surfers all too readily reveal a deplorable strain of human character in their penchant for aggression over something given for free, a gift from nature that we use for nothing more than some momentary euphoria. We surfers forget that waves are living magic. The huge storms, the powerful winds, the great global routes of major groundswells, the graceful curve of protected shorelines and the symmetry of a wave peeling perfectly all combine to give us an unparalleled experience. And what do we do with it? For whatever reason: ego, low self-esteem, selfishness, or professional greed, it becomes all too easy for surfers to ruin our heaven on earth.

How can this be? We are like true believers fighting over who will take communion, pushing and shoving and cutting in line with an infantile "Me First! Me First!" attitude as we approach the altar where our religion is confirmed. And when we finally attain the holy moment and connect with the body and soul of our faith, what do we do? "Mine! Mine!" becomes our mantra. Just ask yourself, "When was the last time you saw a pro surfer get a great wave, but then paddle back out slowly so that others could share in the same experience? When was the last time you saw a local get out of the water so that the waves would be less crowded for others? When was the last time you saw a good surfer give a kook a wave?"

Until these instincts become definitive of our surfing culture, starting with the surf industry and those making a living off the sport, surfing will suffer from a cancerous sore that won't go away. The pro tours, contests, magazines, videos, surf star reunions, big-wave exploits, and guided trips to remote perfection will all mean very little until the leaders of our sport/art publicly make a commitment that says, "Enough! We leave our egos on the beach, and we enter the ocean with humility and a true sense of brotherhood." Until that day, and until the mossbacks and thugs at a hundred spots around the world wise up to what surfing is supposed to be, the next embarrassing episode of surfers as Serbians is just around the corner.

Johny Boy tem fama de mau, mas saiu corrido do Tahiti com o rabinho entre as pernas

Allow me to state my credentials on the subject. I'm writing this in our family room with a view of Oxnard Shores, a place I surfed for the first time in 1968. It is not a wave for the timid when it's good. Top-to-bottom barrels unload over erratic sandbars, and you have to be in good shape to get any waves because the sets can push you up and down the beach a hundred meters at a time. Now that I have lived here going on ten years, I often find myself the first guy out at dawn and one of the few regulars when it starts maxing. So I guess that makes me a local at a place that once intimidated outsiders. Say the word "Oxnard", and the connotation amongst California surfers is pretty negative. But those days are over at the Shores, and that's the way I like it. I want the beach where my children play to be free of the contamination of localism, because I've seen enough of it, and I don't want to see any more.

I've dealt with several versions of "surf rage" during my surfing career in California, including Topanga in the 60s, Silverstrand and the Ranch in the 70s, and Hazard Canyon in the 80s. I've had to face it down in the water and on the beach, and based on personal experience, I've found that surfers "infected" with localism can be surprisingly vicious S.O.B.'s. They can ruin a surf spot in a way that reminds me of floating garbage poisoning the sea.

Modern surfing points to Duke Kahanamoku as its father, yet his aloha version of surfing is about as far as you'll get from the heavy scenes caused by the pools of hate that have floated in lineups around the world: the toxic spills of localism. Of course, if we as surfers look to Polynesia for our heritage, what do we do when we see a history of raids, massacres, and internecine conflict throughout the South Pacific? Are we doomed by cultural genetics to duke it out over our tiny slices of paradise and the short-lived waves we ride?

Polynesian traditions aside, the fundamental problem with surfing will always be how powerfully it drives the ego. There is nothing inherently social in surfing's purest moments, because riding a wave is 100% personal. It is all about your preparation, experience, timing, strength and agility. There is nothing 'team' about it. So cooperation and humility takes a back seat to aggression and arrogance. Left unchecked, it gets to the point that we dare think of ourselves as masters of the waves after a good ride, and we usually paddle back out as fast as we can for another one. As long as you don't have to deal with other surfers and their egos and craving for waves, getting one good ride after another puts a surfer on top of the world.

But as with every powerful experience that involve self-inflation amongst individuals in a crowd, surfing can go from the sublime to the ridiculous in an instant, from euphoria and elation to fear and survival, from a generous free natural environment to a monstrous example of human greed and enmity. Surfers are the blessed sons and daughters of Kahuna gliding through Neptune's kingdom, until they start acting like troops of baboons defending territory against outsiders while engaged in internecine conflicts typical of lower order primate communities.

Another apt comparison would be to the behavior of the sea's most instinctually violent species, predatory sharks. My first experience with a real local, not some land owner or unemployed carpenter or out-of-shape big mouth, was at Lennox Head in Australia, part of the territory of a 15' tiger shark. An apex predator, it feared nothing, and we got out of the water pretty quick the times he was spotted feeding on the larger fish in the area. Sharks are a highly territorial species, in contrast to another apex predator, the broadbill swordfish, well known for its transoceanic migratory routes. Both species developed two hundred million years ago, and have remained essentially unchanged for the past fifty million years. But while the swordfish is an inspiration for speed and agility, the shark conjures visions of merciless pain and death.

So when you consider that some of the worst "surf rage" occurs in some of the world's best waves, it seems that surfing often oscillates between the wondrous hydrodynamics of the swordfish and the brutal turf tactics of the shark. One minute you're flying over the water in a perfect natural setting, only to have the waves turn into the vicious streets of South-Central L.A. As Ice-T said, "Wear a wrong colored rag, go home in a body bag."

Now, surfing is as far from the inner city as you can get. Yet having a colored wetsuit or board that ID's you as an outsider can make for real problems at some surf spots. This is truly absurd. At least in the 'hood there's a reason for the violence: unemployment, fatherless families, poverty, hopelessness. What reason do surfers have to throw down? Surfers are as blessed as any people on earth, and so it is particularly tragic when their egos are controlled by the corrosive evils of selfishness, greed, and jealousy.

I don't know if there is another sport/art/lifestyle on the planet that offers as phenomenal an experience as riding a wave and yet is cursed with human behavior in a classification with sharks and gangbangers. Surfing is an amazing thing to do, but seen through the prism of localism, it comes off looking pretty lame.

Look at surfing as a sport, and consider what it would be like if tennis was similar to surfing. You and I could be beginners just starting to volley when two hot-shot pros could show up and simply muscle us off a public court with taunts and threats while aiming powerful serves at us until we leave. Seen as an art, surfing fares no better. Surfers with bad attitudes are like graffiti vandals with overloaded minds aggressively chasing their fix of identity and recognition. In both versions, the surfing lifestyle is twisted into a joy-less, anxiety-driven fear of outsiders. Based on numerous personal experiences, that's what I've seen happen on the beach and in the water time and again.

My first confrontation with die-hard locals came at Topanga in the late 60s. I worked for Natural Progression in Santa Monica, and since they all rode our boards, they had to tolerate me. But I still got the "Out! Out!" when they saw me walking up the beach. I ignored the warning and got away with it. But when it came to unknown trespassers who didn't pay attention, the warning was followed by rocks and taunts and more rocks. And if an intruder ruined the wave of a local, things got really ugly. Of course, the boys' excuse was that they were defending a good wave from hordes of LA and Valley surfers. But in the end the Topanga locals lost, since all their houses were torn down to make way for a public parking lot and lifeguard station.

The Ranch was a similar situation. Being a boater or a guest, my tenuous connections smoothed the waters to a certain extent. Although the vibe was still in the air, it did not ruin the place for me. Not so for some friends of mine, including Angie Reno, one of surfing's great talents, who in 1971 had to fend off a machete attack from Jeff Kruthers, long time Ranch local who now, ironically, sells Ranch parcels. So I guess if you have the cash, you're in. When I was up there just last year with Rick Vogel and Yvon Chouinard, both parcel owners who have surfed the Ranch for decades, we couldn't surf Rights and Lefts. Seems that given who was out at R&Ls that day, showing up with even one guest was verboten. Yvon put it bluntly, "I don't want my tires flattened again." So we had to settle for surfing in thick kelp at an empty spot a mile away.

The Ranch brand of localism continues to be defined by wealthy owners and their doberman surf bro's. This is in contrast to Oxnard, a working-class town with poverty-driven gang problems and high unemployment. As opposed to the privileged sniffiness of Ranch mossbacks, the worst locals at Silverstrand were usually unemployed construction workers or cholos who didn't even surf. In fact, we quickly learned that surfers in the water were often the least of our problems.

Today it is nowhere near as bad as when we wrote the book on surfing the place by avoiding locals who jacked up the unsuspecting and the innocent. Being "southers" from Santa Monica, we'd park on side streets and chat up residents into watching our cars. In fact, we pioneered the peaks in the middle of the beach because the north jetty parking lot was just too risky. Unfortunately, former Malibu great George Szigeti learned that lesson the hard way. After a great session, he got out of the water only to find four slashed tires and every window of his new VW bus smashed - and a group of thugs waiting for him! So we had to be alert, and although we still had to deal with some real losers, when the waves got big we'd have the place to ourselves.

The Ranch and Oxnard have earned bad reps for localism, but Hazard Canyon, in central California's Montana De Oro State Park, was during the late 80s the worst cesspool of selfishness I ever experienced. Best on cold winter mornings with freezing winds whistling down the canyon, the place is hostile to begin with. With a small take- off zone and a thick, peeling barrel that made drop-ins extremely dangerous, the prevailing atmosphere was intimidating and tense. And since Park authorities were usually miles away, the Canyon was a set up that really stacked the deck against visitors. The regulars were no nonsense tough-guys who could surf the place so well that you wouldn't dare look at a wave they wanted. But even if a local couldn't surf that well, he would still be a factor thanks to his longevity at the place, thick arms from pounding nails, or just plain shitty attitude driven by his own personal failings.

Lead by Whitey and JG, it was a crew that reveled in its reputation for being violent assholes. Bradley Jordan, the best surfer ever to ride the place, took five years and several fights to break into the lineup. I lucked out: I knew Bradley when he was a grommet hanging around the NP shop in the Santa Monica days, so I gained entry through him. No one ever got in my face, although what I saw and heard directed at innocent strangers made me cringe more than once in the three years I surfed the place.

As it turns out, I went back a few years ago, and things had changed to a certain extent. Whitey was still whining, the takeoff zone was tight with carpenters and roofers with attitude to spare and the waves were merciless if you made a mistake. Yet, the threat of violence did not hang heavy in the air, as if the crew had finally wised up a little bit.

But unfortunately, the primal instinct of localism rarely goes away on its own. Consider the Rockside boys of Port Hueneme. Their surfing traditions came from a tainted gene pool where localism was handed down from a generation of has-been longboarders to young high school dropouts turned wanna-be surf stars. These guys were real jerks - until one of their homies was convicted on assault charges when he attacked a teacher from Santa Monica surfing an empty peak west of the pier. The guy got probation that prevented him from surfing the place for three years. But genius that he was, he was right back in the water a few weeks later, only to have a cop pulled up as he was getting out of the water who took him straight to jail to do his time for the assault and violating probation. It was poetic justice that a Rockside rockhead did time for being not only violent, but stupid, too.

The fact that a surfer was put behind bars for being violent says that the worst of the localism as I've known it is on the retreat. One reason that things are changing is California Penal Code sections 243 and 245 dealing with aggravated assault. Victims are now calling the police, and in recent years the law has stepped in to protect the innocent and charge the guilty. Witness what happened in Palos Verdes or the assault in San Diego two years ago. Guys got arrested and convicted, and newcomers were able to surf without threats from mossbacks giving 'em stink-eye and worse.

Another reason that "surf rage" is abating somewhat is the fact that yesterday's surf hoodlums have grown up and now have kids, and if there's one thing that's going to change the life of an OG (LA slang for 'original gangster'), it is having to be a father. A third reason for localism's overall decline is that, over the past five years or so, dilution has been the solution to the pollution of localism. There are now so many surfers everywhere that, as when Topanga was turned into a public beach, who is or isn't a local is now a moot point. Like King Canute ordering the tide to stop, the hard-core locals of yesterday are being sweep into submission by a constant tide of recreational surfers spreading around the world.

Riding a wave is a perfect opportunity to test our human nature, face up to our failings, and focus on bringing out the best in ourselves. Consider the non-violent example of Ghandi. He understood the devastating effects of an unchecked ego. For ten years he resisted becoming the leader of India's independence movement until he felt ready to be a powerful, yet selfless, man of inner peace. His autobiography, "The Story of My Experiments with Truth," is a wonderful inspiration in dealing with the subjugation of ego.

Locais de verdade

This is good news. Surf spots are extra special natural environments because they give people a chance to play with the ocean's energy. There is no cause for selfish and sometimes violent behavior over waves that belong to no one. As the legendary North Shore surfer Owl Chapman once said, "Be nice, share a wave, give a smile, say Hi". I couldn't agree more: a friendly vibe in the water makes the surfing experience complete.

So the next time you're tempted to vibe someone you don't know or take more waves than you deserve, consider things from the other guy's point of view. Only when courtesy and sharing define our behavior is it possible to fully realize the promise of surfing. Show some respect for Mother Ocean and leave your ego on the beach. If you're a visitor, the same rule applies: don't be confrontational, but at the same time, remember that you owe the ocean a lot, so don't turn tail and retreat without trying to work things out verbally. Localism is a toxic spill that has contaminated a lot of surf spots, and sometimes you have to help in the clean up.

If you really have surfing in your heart and soul, you simply have to act in the name of civility in the water, starting with an attitude of cooperation and sharing. If it's too crowded, get out of the water and wait on the beach, or surf someplace else. Battling the pack endlessly brings out the worst in people. Same goes for any territorial feelings you might have about your favorite surf spots. There is no excuse for desiring euphoria so much that violence becomes a way to get it. This aspect of surfing simply has to change, and that's all there is to it.

As Charles William Maynes recently said with reference to Bosnia and Kosovo, "Society . . . depends on deference, deference to tradition, authority, to law, to treaty commitments. If you lose that, the only thing you've got left . . . is force." In surfing, we have no governing authority, and the times we've resorted to criminal law to resolve our disputes have been excruciating embarrassments to the sport as a whole. So we must defer to each other in the water and respect the best traditions of riding waves: the traveling, the welcoming of visitors and the sharing of waves exemplified by the early longboarders. Thus, we must commit to personal treaties of peace with all our fellow surfers if any of us is to truly deserve the joy to be found in surfing.

Yelling to get waves, challenging guys to fights on the beach, pushing off shoulder-hoppers, giving strangers stink-eye, dropping in on kooks: Lord knows I've seen and done my share. But let me tell you from personal experience: a surfer's soul feels much better when you really make a pacifist attitude a part of your surfing identity. Always being generous and cooperative, especially when the waves are good, can be a long, and difficult lesson to learn: ask Nat or Johnny-Boy. But if we all behave as if our children are watching us surf, we will someday cleanse the stain from surfing's soul, and the localism and violence of modern surfing will be nothing more than sad chapter in a distant past. I may not see it, but if there's anything I can do about it, my children will.

* * * Glenn Hening started the Surfrider Foundation in 1984. He currently publishes an annual "Groundswell Society" covering ideas and projects of interest to "Renaissance" surfers. This article first appeared on SURFLINK.com. Sections of it were developed for a series of essays that appeared in the second edition of Glenn Hening's Groundswell Society Annual Publication. The third edition is in the works and will be available this fall. Contact Glenn for more information at GRNDSWEL@aol.com

Greetings,

ResponderExcluirWell put

information:) Found this here on julioadler.blogspot.com [url=http://easyrvoutdoors.com]RV[/url]